Federal Debt Crisis Not in the Cards

Long-overdue corporate tax reform has finally arrived. It promises to improve the global competitiveness of U.S. corporations and boost job creation on the home front, fueling the growth of exports. For stock investors it should lead to improved earnings growth. For bond investors it makes corporate borrowing less attractive – which could reduce borrowing demand and slow the rate at which yields climb as the Fed normalizes monetary policy.

Still, the upside to corporate tax reform is overshadowed by its price tag: an estimated increase in Federal debt of as much as $1.5 trillion dollars. Some investors are concerned: are we setting ourselves up for a day of reckoning? Before answering that question, let's dig a little deeper.

Prior to tax reform, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) had forecast that the Federal debt would grow from $20 trillion to $30 trillion over the next 10 years. That projected increase is due mainly to the retiring baby-boom population, which is just beginning to draw on Federal entitlements such as Social Security and Medicare. Their ranks will grow over the next 10 years. Tax Reform is expected to add up to $1.5 trillion to the Federal debt over that period, boosting the 2027 projection to as much as $32 trillion.

It's a big number, of course, but a little perspective is in order. Total household net worth – everything that U.S. citizens own net of debts, including property, investments, and cash – is nearly $100 trillion today, and will likely grow to around $150 trillion by 2027. GDP, an annual measure of total U.S. economic output, is $19 trillion today and will likely grow to $28 trillion by 2027.

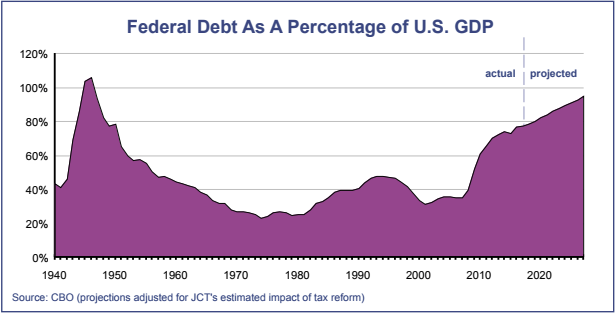

Traditionally, the portion of the Federal debt that's held by the public (about $15 trillion today) is compared to GDP, as shown in the chart on the next page. GDP is a measure of economic output that can be taxed, so it serves as a proxy for tax revenue. Thus, a government's ability to service its debt is largely determined by the size of the economy that is generating its tax revenue.

But GDP is not the only thing that gets taxed; the U.S. tax system also captures a piece of household net worth too. This is accomplished mainly by capital gains tax on property and investments, but it also includes tax on IRA distributions, gifts, and inheritance. So in reality, U.S. tax revenues are tied to both GDP and household net worth.

Fortunately, after a dicey period following the Financial Crisis, both of these sources are now robust and growing. As exports ramp up and energy imports wind down, the U.S. trade balance should swing positive sometime before 2027. That would set the stage for GDP, tax receipts and household net worth to climb about 50% between now and 2027.

Federal debt held by the public (as a percent of GDP) will still grow over the next 10 years, meaning it will be slightly more difficult to service than it is today. But by 2027, a much larger base of exports could boost tax revenue enough that Federal debt would plateau after that.

Right after the Financial Crisis, a widely reported study claimed to have statistical evidence that government debt levels above 90% of GDP would weigh heavily on long-term growth. But that study ultimately turned out to have flaws – in reality, there is little correlation between economic growth and government debt levels. Last year, we saw a dramatic example of a heavily indebted economy bouncing back from a deflationary slump. Japan, despite an overwhelming debt load (240% of GDP), and a newly imposed 8% national consumption tax, is rebounding thanks to its quantitative easing program and a recovering global economy.

Finally, it's worth noting that the U.S. "debt-to-equity" ratio is not particularly onerous.

Measured against household net worth, it's roughly 20% today and seems unlikely to climb above 25% in the next decade. Most S&P 500 corporations carry significantly more debt (although their entitlement liabilities are much lighter). At a time when inflation remains well controlled thanks to technology disruption, the interest payments on the Federal debt are not likely to become a major budget item until well after the Fed has shrunk its balance sheet and the U.S. trade balance turns positive.

Moving Into Trade Surplus

And once the U.S. trade gap has closed, the potential for debt-related economic disruption would be sharply diminished, for several reasons:

- The Federal debt would once again be held largely by U.S. citizens, because foreign governments would sell off their Treasury holdings as their trade surpluses disappear (the amount of Treasuries held by foreigners has already fallen by 50% since 2009).

- The U.S. should be self-sufficient in energy, agriculture, autos, aerospace, and housing. Plus, infrastructure costs may be falling – thanks to new technologies that allow private firms to relieve the government of its obligations in transportation and energy.

- A relatively small sales and services tax (below that of Canada's 5% GST) could easily generate a very large amount of tax revenue with little impact on the economy (if we need it).

Even if the Federal government did get to a point where it struggled to pay its bills, chances are the dollar would still hold its own, since it would represent a robust self-sufficient economy that in aggregate throws off more capital than it consumes.

Investment Implications

By taking on additional debt over the next 10 years, the Federal government is making an investment in the competitiveness of the American economy. Private wealth, by definition, will grow as much as Federal debt does, with the stock market likely registering a significant share of that increase. As such, it's probably unwise to use Federal debt as an excuse to reduce stock market exposure or to hold on to an excessive amount of cash.

Fourth Quarter Review Stocks surged in the fourth quarter as the global economy continued to recover, and as U.S. tax reform efforts gained traction. Also helping was the Fed's announcement that its current plan for normalizing short-term interest rates did not need revision, as tax reform is not expected to meaningfully boost inflationary pressures. The unwinding of the Fed's balance sheet had very little impact on the bond market, which was far more focused on the potential impact of tax reform. And earnings remained on a favorable trend even prior to tax reform effects.

The S&P 500 gained 6.6% for the fourth quarter to finish the year with a 21.8% gain. The Barclay's U.S. Bond Index edged up 0.4% for a full-year return of 3.5%. The sector side of our stock-oriented holdings finished on par with the S&P 500 for the quarter and ahead of the index for the year, whereas our diversified stock positions finished just shy of the index for both periods. On the bond side, our emphasis on high-yield and shorter maturities didn’t provide any advantage in the fourth quarter, but we finished ahead of the Barclay's benchmark for the year.

Outlook

Many investors think that the stock market has become expensive, but based on operating earnings today's S&P 500 P/E ratio of 21.4 is almost exactly where it was a year ago. In effect, all of the capital appreciation we've seen has been based on improved earnings. In the coming year, we may see more of the same. The impact of tax reform has yet to be factored into 2018 earnings forecasts, which were already looking rather robust.

So what can go wrong? As usual there are a lot of little things to worry about: higher interest rates, a Fed that might become more hawkish, a surge in the dollar from repatriated foreign cash, a slowdown in consumer spending from residents in high-tax states, an increase in high-yield default rates stemming from reduced tax allowances for debt-service expenses, and a growing Federal debt load (which we've already discussed). At this stage, however, all of those risks seem to be manageable.

As such, we're not looking to make major portfolio changes for 2018. On the sector side, we're sticking with overweighted positions in technology and financial services, while looking for an opportunity to boost consumer discretionary exposure. Among diversified stock holdings we have reduced our small-cap positions in some portfolios, choosing instead to favor large-cap growth stocks, both domestic and foreign. Bond-wise we remain focused on corporate debt, which may see a supply reduction, and where taking on extra credit risk can help boost yields.

Sincerely,

Jack Bowers

President & Chief Investment Officer